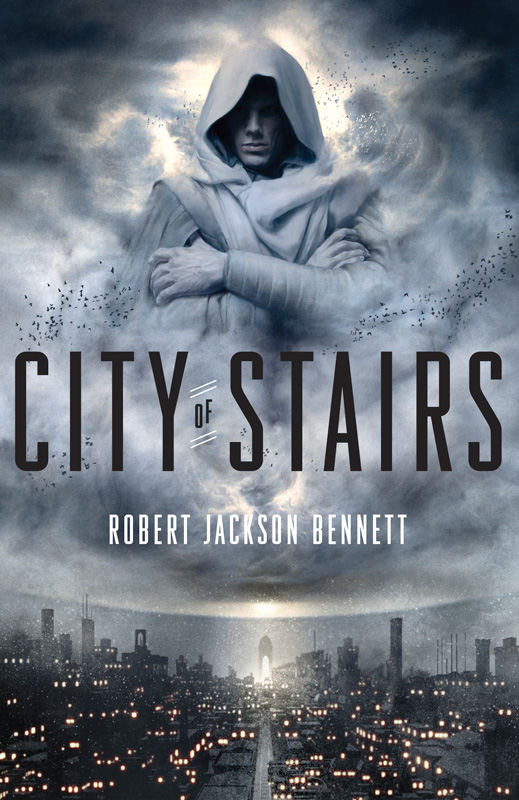

Robert Jackson Bennett’s City of Stairs—available now in the US (Crown Publishing) and October 2nd in the UK (Jo Fletcher Books), and excerpted here on Tor.com—is both a murder mystery and fantasy novel.

A spy from Saypur, a colonial power, is investigating the murder of a historian in Bulikov, an old city that is one of Saypur’s colonies. The murder investigation, however, requires the spy to deal with the histories of Saypur and Bulikov themselves; along the way, she discovers that Bulikov’s dead gods—deities on earth defeated in warfare when Bulikov fell to Saypur—may not be exactly dead after all.![]()

I recently talked to Robert Jackson about this new direction in his writing.

Brian Slattery: Maybe the best way to start talking about City of Stairs is to talk about American Elsewhere, a book I keep recommending to everyone. American Elsewhere invigorates the conventions of a horror novel by adding some shades of what I read as Cold-War-era, Area 51–style SF lore. Did this blend of elements come to you fairly naturally or was it built into the idea

before you started writing it?

Robert Jackson Bennett: Looking back on things, it does feel like my first four novels—of which American Elsewhere is the fourth—are sort of a series of reflections on the American past.

Mr. Shivers examines the Great Depression, The Company Man looks at urbanization and industrialization, and The Troupe is a reflection on vaudeville as what might be the first truly American art form, or the first time art was able to cross-pollinate across all of the American regions.

American Elsewhere is kind of my final statement on this part of my writing career, I think. It’s a culmination of a lot of things I’m obsessed with: I remember listening to Tom Waits’s “Burma Shave” and looking at Edward Hopper paintings and wondering exactly why this felt so distinctly American, this blend of desperate, sentimental hope paired with intense, lonely alienation. It’s something that, in my head, and maybe in our own cultural heads, is baked into the 40s and 50s, twinned with this idea of the sudden proliferation of “the Good Life,” the Leave it to Beaver rewriting of the American family. And still all of that is tied up the Cold War, with the space race and this sudden feeling of possibility—that the future could be fantastic and utopian, or it could be little more than radioactive ash.

I kind of wanted to throw all of that into a blender and look at it from as alien a lens as I could possibly imagine—and suddenly I wondered what Lovecraftian monsters would make of this amalgam of images and pretty lies that make up the heart of this nebulous thing we refer to as the American dream.

BS: To someone following your career, a move into fantasy doesn’t seem all that unlikely. So it’s interesting that you mentioned yourself that you would “never set anything in a second-story world, chiefly because I always felt these sorts of things were kind of, well, a big pain in the ass.” Then you went on to say that “I’ve never been happier to be proven wrong—I’m having a tremendous amount of fun.” Can you flesh this out a little bit? Why did you shy away from a book like this? What changed your mind? And once you dug into it, what did you discover that a fantasy book could let you do that you hadn’t been able to do before?

RJB: Well, to be fair, it is a big pain in the ass. To maintain this world, I have to carefully curate what is now an eleven-page Word document consisting of a 2,000 year timeline, along with varying names of the months, the days, the religious texts. This would be a pain in the ass to maintain even if it corresponded with a real-world history (imagine a Word document summing up the Tudors), but when the burden rests on me to provide the name of the book or town (or whatever), and make sure it’s consistent with all the other books and towns I’ve mentioned thus far, then suddenly I have to think very long and hard about this tossed-off mention of a thing in a single line of the book that has no long term consequences on the plot whatsoever.

But it actually is quite a bit of fun. What I’m describing are the most boring bits, the parts I like the least, but I also get to do all kinds of fun things, where the way the miracles work and the ways the cities are structured reflects what I feel to be the nature of our own real world, only distorted. Fantasy offers us the opportunity to take the limitless contradictions that confront us in our world and set them against one another, thus allowing us a rare peek into what makes these contradictions both so ridiculous and so desperately human.

BS: You also said that City of Stairs is “inspired by many real-world things, but is more or less made up entirely by me.” What real-world things did you find yourself drawing from? And at what point did you leave these real-world inspirations behind to run with the ideas that emerged?

BS: You also said that City of Stairs is “inspired by many real-world things, but is more or less made up entirely by me.” What real-world things did you find yourself drawing from? And at what point did you leave these real-world inspirations behind to run with the ideas that emerged?

RJB: I’m a bit of a foreign policy wonk, and the past year and a half or so feels pretty remarkable in the global spectrum. People say every day that it feels like the world is on fire, like the world has gotten suddenly smaller, suddenly faster, or both. This idea—a world that shrinks overnight—is realized literally in the book.![]()

The tropes of the book are pretty solid and old school. The realist, selfish foreign policy, the old spies who grow disillusioned with their agency—that’s pretty timeworn. But with Snowden in the backdrop, and Ukraine, and the whole world casually looking on as Syrians slaughter one another, suddenly what was once old feels very new again. They’re tropes for a reason. And now, well after the book was written, we have ISIS, and Hamas and Israel, and countless other brutal tragedies.

These things have all influenced how the way the politics function in the world of City of Stairs. Syria, especially: Saypur is more than happy to sit idly by while the Continent eats itself alive. Sometimes what seems like inhuman indifference can seem like a very viable policy option, depending on what desk you’re sitting behind.

But it is worth saying that my fictional world can’t hope to catch up to the real world. The world of City of Stairs is boiled down to the relationship between two very large nations. In the real world, even large nations feel terribly small and powerless in the context of global conflicts. And unlike City of Stairs, many times in the real world there are no good options, and no solutions whatsoever.

BS: Though it represents a new phase in your career, City of Stairs also has a fair amount of continuity from American Elsewhere—the idea that, to borrow a phrase from Doctor Who, things are bigger on the inside. In City of Stairs, the old city of Bulikov is bigger than the new city, and yet still exists inside the new city. The gods and other creatures of the old world are large things trapped inside small containers, and havoc is wrought when they’re unleashed. They’re too big for the smaller world that exists in the present. I see the same dynamic in the way your characters relate to history, both the history of the world they live in and their own personal histories. I think one of the reasons early readers have attached themselves to Sigrud is because he perhaps embodies this best: You suggest a vast personal history for him, the sense that he’s lived and died a thousand times, done great and horrible things that most of us—and most of the other characters—would only dream (or have nightmares) about, and this aspect of him, even more than his physical appearance, makes him larger than life. What do you think draws you to this idea? What does it let you do in your stories?

RJB: What I think you’re describing is the literal realization of the mysterious: the idea that there is more than what you are experiencing, or even what you could experience. There is the house that “just keeps going” in American Elsewhere, and in The Troupe there’s the office of Horatio Silenus that conveniently happens to exist in whichever hotel he’s staying at, provided he walks down the halls in the right way. Chris Van Allsburg is sickeningly, sickeningly good at this, and The Mysteries of Harris Burdick and The Garden of Abdul Gasazi are two examples of the mysterious that made my brain overheat as a kid.

This, to me, is one of the most wonderful feelings you can get out of fiction. Suggesting that there is more past the border makes your brain feverishly go to work wondering what’s there. That’s what a mythos and a canon is all about, this idea that behind all the pages you’re reading, there is a vast and untouched history just waiting to be explored. There’s nothing more mysterious than the past, nothing more strange and curious than the tale of how we got to where we are.

Can’t get enough of Robert Jackson Bennett? Check out his Pop Quiz interview to learn everything from Robert’s favorite sandwich to his Hollywood pick to play Sigrud, plus listen to the Rocket Talk podcast episode in which Bennett discusses the future of genre fiction!

Brian Slattery is an editor, writer, and musician. His latest book, The Family Hightower, is also out on September 9. This is a total coincidence.